Ship Propellers – How Do They Work?

The propeller is the driving force behind most of the world’s ships and aircraft. It propels large commercial ships through the water at 15 knots and propels commercial aircraft at 550 mph. But how does it work? Today, we’ll look at how Ship Propellers work, some of their designs, and how they differ from aircraft propellers. We’ll also look at an alternative that could make Ship Propellers obsolete.

Propeller Basics

Propeller design affects every aspect of a vessel, from “maneuverability, ride, comfort, speed, acceleration, engine life, fuel economy, and safety. The propeller is second only to the power provided by the engine itself in determining a vessel’s performance,” according to Killcare Dock. A seemingly simple device can have a dramatic effect, depending on the shape, size, angle, and number of blade tips.

First, the basics: Does a propeller push or pull water? The answer is a bit of both. Similar to the way a household fan draws air in from the back and pushes it out the front, as fans spin, they push water back, creating a space in front that water has to rush into to fill. It pulls water in and pushes it out to create forward momentum.

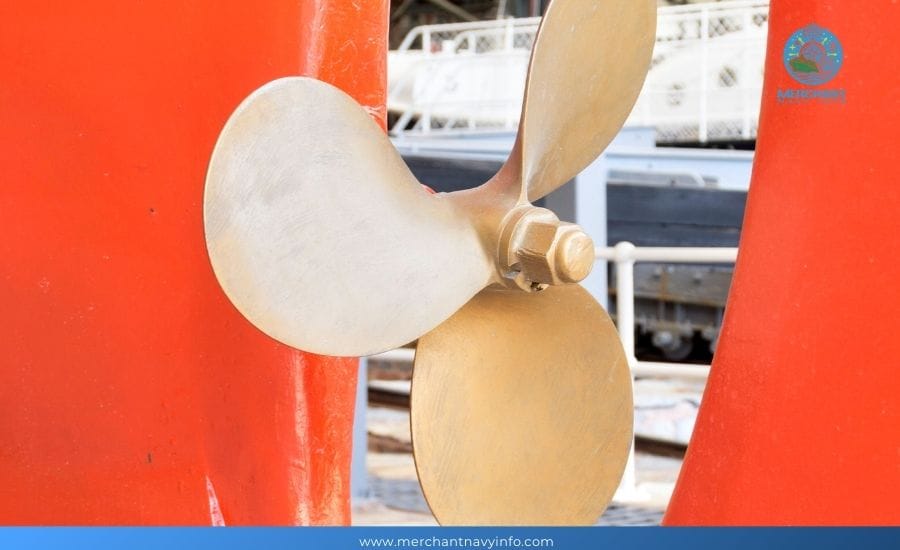

Each blade has a pressure differential, creating positive thrust pressure at the bottom of the blade and negative drag pressure at the top. Most propellers have three or four blades (although they can have more), and each blade creates these forces simultaneously. Pulling water in and pushing it out at higher speeds creates thrust, which moves the boat through the water.

The process can be more easily visualized using an azimuth propulsion pod, which combines the functions of a propeller and a rudder to provide 360-degree movement. Water is sucked in at the front of the impeller and pushed out at the back, and the whole thing can be rotated to provide thrust in either direction.

A thruster is a propeller inside a rudder for added flexibility. The downside to this setup is that it is not cost-effective for ships that spend most of their time cruising at low speeds on the high seas, such as container ships. These ships are built for maximum efficiency and are usually equipped with a large fixed propeller that provides only one direction of motion, which can then be adjusted with a rudder. The sheer size makes it a relatively fuel-efficient ship, but the single propeller and small rudder result in poor maneuverability.

What parts does a fan consist of?

Each part of a propeller has a name, and here are some terms for those tech geeks who want to know their propellers (tech geeks are cool!):

The front part of the blade that sucks in water is called the leading edge, the part behind the blade where the water is expelled from the propeller is called the trailing edge, and the outside part where these two parts meet is called the tip of the blade. The cup is the small curve on the leading edge that helps the blade retain water.

The front of the blade is the side facing away from the bowl, creating positive pressure, while the back faces the bowl, creating negative pressure. The root of the blade is the bottom part of the blade, which is connected to the outer shaft. The inner shaft is connected to the shaft that turns the propeller.

Propellers have a few other special parts, and if you’re interested in learning more about them, check out Killcare Marina’s excellent article, which goes into great detail.

So, how does fan design affect its operation?

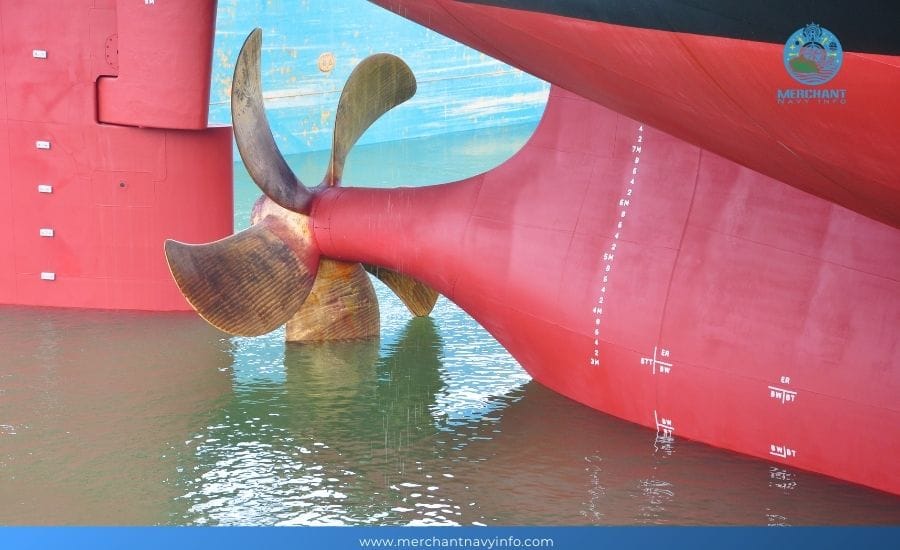

The simplest way to categorize fans is by their size. The propeller diameter is the distance between the edges of a circle drawn around the blade’s tip. This diameter can be as small as 1.25 inches for a Traxxas Blast RC boat or as large as 9.6 meters (31.5 feet!) for one of the largest container ships, the Emma Maersk.

An Emma Maersk propeller weighs 131.4 tons, or (according to Survival Tech Shop) more than a small house! The correct propeller diameter depends on several key factors, including RPM, the power being delivered, the desired ship speed, and whether the propeller is a partial surface. Generally speaking, slower ships use larger propellers, faster ships use smaller propellers, and more power generally means a larger propeller.

Killcare Marina says the pitch is similar to the pitch of a screw, and it measures the distance a propeller moves through a soft, solid material. A 16-inch by 22-inch propeller has a 16-inch diameter and moves 22 inches forward in one full rotation. Poor manufacturing and damage can affect pitch. There are two common types of pitch: Flat pitch means the blades are flat and the speed is constant.

Killcare Marina says the pitch is similar to the pitch of a screw, and it measures the distance a propeller moves through soft, solid materials. A 16 x 22-inch propeller has a 16-inch diameter and advances 22 inches in one rotation.

Poor manufacturing and damage can affect pitch. There are two common types of pitch: Flat pitch means the blade is flat and at a constant angle from the leading edge to the trailing edge. Progressive pitch means the blade starts with a smaller pitch at the leading edge and gradually increases to the trailing edge. Progressive pitch improves performance in higher horsepower applications or where the propeller may break through the water. It acts like another set of gears with a greater pitch, creating a taller gear – the pitch must be correct for the application.

The number of blades can also affect the boat’s performance. A single blade is the most efficient setup, but it produces a lot of vibration. Three or four blades are the most common, as they are the best compromise between efficiency and vibration reduction.

Most large boats and propellers use four blades, but five are sometimes used. Many other factors, such as blade thickness, angle of attack, and even blade shape, must also be considered when choosing a propeller. This Killcare Marina article has much information if you want to learn more!

What is the difference between a boat propeller and an airplane propeller?

Boat propellers typically have wide, thin blades that spin relatively slowly. Aircraft propellers, or propellers as they are sometimes called in the UK, use narrow, thick blades that spin very quickly. Wider, slower-spinning blades work well in water, while thinner, faster-spinning blades work better in air.

Why is this? According to Explain That Thing!, the easiest way to think about it is that a propeller moves an object forward through a fluid. Since seawater is about 1,000 times denser than air, you need to move more air to create the same thrust as in water. Aircraft also travel much faster than ships and rely on that speed to stay in the air, while ships float on the water and move much more slowly.

The average speed of a container ship is about 14.75 knots, or about 17 miles per hour, while the average passenger plane you take on vacation travels at about 550 miles per hour. These very different requirements require different propeller sizes, shapes, and angles.

Propeller materials also differ between the sky and the sea. Ship propellers must handle salt water, which is highly corrosive to many materials, and alloys such as copper are often used. Aircraft can use various exotic materials and manufacturing methods, such as magnesium alloys, hollow blades, and wood composites.

Ships also have to deal with cavitation, where propellers running under heavy loads create vapor bubbles that form and explode next to the propeller blades, forming tiny craters and eroding the surface.

A future without fans?

According to Explain That Stuff!, Archimedes first came up with the idea of using a screw to move water up a cylinder in the 3rd century BC. This method is still used today in harvesters and factories. Leonardo da Vinci designed a propeller for a helicopter in the 16th century, but it was never built.

In 1796, American inventor John Fitch built the first rudimentary propeller for a ship, and then Francis Pettitt Smith and John Erickson independently invented new designs, and the modern propeller design was introduced in 1836. In 1903, the Wright brothers used a twisted propeller to make the first powered flight. The idea of using a screw to move objects is more than 2,000 years old, and the modern propeller is nearly 200 years old.

Is it time for a change? A recent article in The Economist made an interesting observation: “No marine creature is known to use a propeller.” It’s an interesting observation, but what other solutions are available for boats? Most boats use propellers, and larger propellers are more efficient, but you have to worry about the propellers getting tangled and hitting underwater obstacles. Flippers and fins are the evolutionary choice for aquatic propulsion; almost all marine fish and mammals use them.

Benjamin Pietro Velardo is working on using flexible materials to change the way we move in water. His company, Pliant Energy Systems, has developed a prototype based on a squid: with flexible fins on both sides, it can move under water, on water, and even on mud or ice. The results are already impressive, as the prototype “produces about three times more thrust per unit of energy consumed than a typical boat propeller,” The Economist reports.

The new tracking vehicle, called c-Ray, will be autonomous and initially used for mine detection, surveillance, and patrolling. This wave propulsion does not produce cavitation like a fan and is quieter during operation. It has the potential to be expanded to full-size submarines and other large vessels as a more efficient and quieter form of propulsion. It could also provide charging capabilities if held in place as waves move the fins.

Velox Flexible Power System

Propellers are used on everything from small boats to fighter jet engines. While it’s not going away anytime soon, seeing new technology that can make ships more efficient is exciting. For now, the only changes we’re likely to see shortly are different materials and designs. The new thrusters are particularly interesting because they’re being used on dynamically positioned vessels, and OneStep Power is testing DP2 and DP3 vessels to see how they fail in the event of a short circuit.