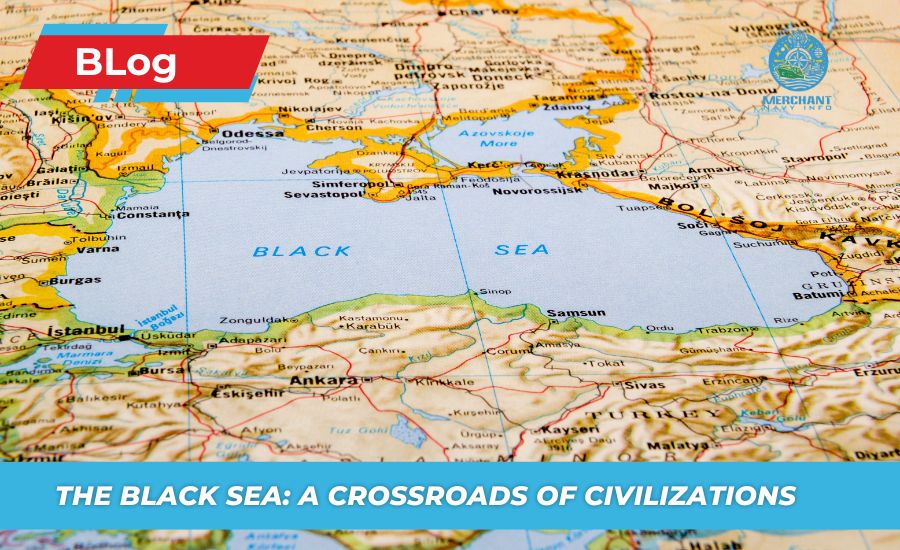

Geostrategic Importance of the Black Sea Region

Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in March 2014 has refocused global attention on the strategic importance of this region, which lies on the fault line between two former empires, the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire, and involved European powers such as Britain, France, Turkey, and Germany. This analysis provides an overview of the region, arguing that the past is a precursor to the region’s future while reviving the volatile power of experimental political and military strategy in a modern context.

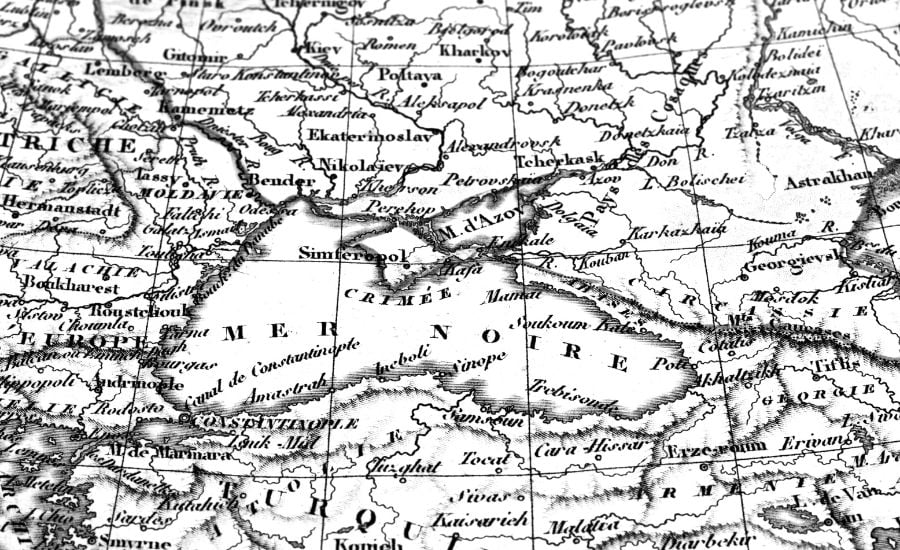

Six years of conflict between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, from 1768 to 1774, culminated in the signing of the Treaty of Kuchuk-Kainalga in 1774. This treaty granted Russia direct access to the Black Sea region (via the ports of Kerch and Azov). Russia was also granted the right to protect the Ottoman Empire’s Christian minorities, and the nominally independent Crimean Khanate was also affected by it.

Nine years after the treaty was signed, popular dissatisfaction with the reforms introduced by Russia’s captured ruling elites and a steady influx of settlers into Crimea fueled regional unrest. It provided a long-standing pretext for Catherine II’s envoy, Prince Grigory Potemkin. It waited to annex Crimea by military means, with little armed resistance. In the same year, the city of Sevastopol in Crimea was founded, and from 1783 onwards, as the Ottoman Empire gradually began to decline, Russia gradually rose in the Black Sea.

The decline of the Ottoman Empire continued, as did the power struggle in the Black Sea region, with neither side achieving a decisive victory. The bloody Crimean War, which lasted from 1853 to 1856, killed hundreds of thousands of people. France and Britain sided with the Ottoman Empire during the conflict, fearing that Russia’s growing power would lead to Russian dominance in the region.

Although this goal was never achieved, a stronger and more isolated Russia repeatedly failed to wrest control of the strategic Bosporus and Dardanelles (Turkish Straits) from the Ottoman Empire. One of Russia’s main motivations for World War I was to seize control of the Turkish Straits, but this backfired when the Ottoman Empire and Germany blocked the straits and strangled the Russian economy.

During and after World War I, after the collapse of the Russian and Ottoman Empires, attempts were made to redraw the map of the region, but they were unsuccessful. The first attempt was the Treaty of Sevres in 1920, and the second and more successful attempt was the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, which laid the foundation for the Turkish Republic.

Having achieved a more secure strategic position, Turkey was able to use the Treaty of Lausanne to counter the growing tensions between European powers in the region, culminating in the 1936 Montreux Agreement, which established Turkish control of the straits and guaranteed Turkey’s freedom of passage for warships of Black Sea countries that were not at war with Turkey. Restrictions were placed on non-Black Sea littoral countries sending warships into the Black Sea (each warship must weigh no less than 15,000 tons, or 45,000 tons total, and must not stay in the Black Sea for longer than 21 days). The United States is not a party to the Montreux Convention.

Post-World War II and post-Cold War regimes

This fragile balance threatened to be upset when tensions flared between the Soviet Union and Turkey at the end of World War II. The Soviet Union pressured Turkey to renegotiate the Montreux Agreement to share control of the Bosporus and Dardanelles with Turkey. In 1946, the Soviet Union increased its military presence in the Black Sea and pressured the Turkish government to accept the establishment of military bases on Turkish territory.

To protect itself from Soviet pressure, Turkey requested assistance from the United States, which responded by sending American warships to the region. Although the Soviet Union eventually backed down, the incident was one of the impetuss for the Truman Doctrine in 1947, which sought to curb the growing Soviet threat in the Mediterranean by making Turkey and Greece members of NATO by 1952. An uneasy balance exists between Turkey, NATO, the United States, and the Soviet Union in the Black Sea region. From 1976, Turkey allowed Soviet aircraft carriers built by Ukraine (Kiev class, later Kuznetsov class) to pass through the straits.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the geostrategic importance of the Black Sea region declined from a Western perspective. Still, it remains an effective tool for shaping the concept of Russia’s “near abroad”. The most important strategic issue after the end of the Cold War was the removal of nuclear weapons from Ukraine, which was reflected in the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, in which Ukraine agreed to remove nuclear weapons in exchange for security guarantees from Russia, the United States, and the United Kingdom (supported by France and China) to protect its territorial integrity.

Despite the success of this policy, Ukraine and Russia continue to have a turbulent relationship over the strategic Crimean Peninsula. Given by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in 1954 as a gift to mark the 300th anniversary of Ukraine’s merger with Tsarist Russia, Crimea has become a constant bargaining chip between the two countries. Russia has retained military infrastructure, especially the base in Sevastopol, which is essential for the operation of the Black Sea Fleet.

At the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union, there were 100,000 Russian soldiers, 60,000 military personnel, and 835 ships, including 28 submarines, which were effectively used to pressure Kyiv on the legal status of Sevastopol and its key infrastructure. Moscow, also fueled by Crimean nationalist fervour, was able to leverage its enduring political ties with Crimean officials (Crimea retained autonomy and its constitution until 1995) to increase pressure on Kyiv.

The 1997 Ukrainian-Russian Friendship Treaty divided the Soviet Black Sea Fleet between Russia (81%) and Ukraine (19%) and allowed Russia to lease the Sevastopol base for 20 years, extended in 2010 to 2042, in exchange for the cancellation of most Ukrainian debts and lower energy prices.

The Emergence of the New Russia

While Russia has always considered its former Soviet republics and the Black Sea region to be within its natural sphere of influence, it lacks the political, economic, and military power to impose its will fully. This began to change as Russia adopted a more assertive regional policy in response to the so-called colour revolutions that took place in Russia’s neighbouring countries of Georgia (the Rose Revolution of 2003-2004) and Ukraine (the Orange Revolution of 2004-2005), where leaders more susceptible to influence and interest were replaced by pro-Western, pro-European, and pro-Atlantic leaders.

At the same time, in 2004, NATO membership was expanded to include Bulgaria and Romania, resulting in three of the six Black Sea littoral states joining NATO, with two more, Ukraine and Georgia, working closely with the alliance with the potential goal of…NATO membership. NATO considers the Black Sea “very important for Euro-Atlantic security” (Bucharest Summit Declaration, 2008).

Russia considers these events as NATO encroachments on its traditional sphere of influence and has taken steps to reestablish its influence and strengthen its military presence in the Black Sea. Russian energy was previously used as a tool to influence Ukraine in 2006 and 2009 when Russia temporarily stopped gas supplies to Europe through Ukraine and increased Russian energy prices.

In August 2008, Russian troops, who had been in South Ossetia since the outbreak of the conflict between Georgia and South Ossetia in 1993, successfully thwarted the Georgian president’s attempt to retake control of the breakaway region, then entered Georgia, crushed the Georgian army and nearly seized control of the capital, Tbilisi (about 350 soldiers and 400 civilians died on both sides of the confrontation). Russia ignored the ceasefire and recognised the “independence” of South Ossetia and Abkhazia soon after, and has since strengthened its control over Georgian territory and continued to integrate the two regions administratively.

Why Black Sea is Important to Russia?

The second event of greater geostrategic and military significance was Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014, days after Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych was overthrown in a popular uprising in the spring of 2014. This violated the Budapest Memorandum and the Treaty of Friendship.

Russia’s remilitarisation of the peninsula and military intervention in eastern Ukraine paved the way for a massive military reinforcement of the region, with the deployment of S300 and S400 systems, Bastion-P coastal defence units, and other anti-air and anti-surface missile systems. Former Supreme Allied Commander Europe, General Philip Breedlove, described Crimea in 2015 as a “platform for Russian power projection.” The entrenchment of Russian forces on the peninsula was accompanied by increasingly aggressive nuclear rhetoric, with the Kremlin hinting at the possible future deployment of nuclear weapons on the peninsula and stating that it reserved the nuclear option to defend Crimea if necessary.

The final step in restoring Russia’s military presence in the region was Russia’s military intervention in Syria in September 2015. Russia demonstrated its ability to deploy its Black Sea Fleet for the first time since the end of the Cold War, deploying both its Black Sea Fleet and its Maritime Fleet, as well as defensive (S300) and offensive (SS-26) systems in the theatre. Russia currently operates an air base in Latakia, Syria.

It is currently renovating and expanding its naval facility in Tartus into a larger base capable of accommodating up to 11 ships at a time. It also has an agreement with Cyprus to allow Russian ships to dock and is currently negotiating a military base in Egypt (Russian officials have denied rumours about Libya).

The return of the Black Sea’s geostrategic importance

Russia, the 19th-century hegemon, depleted during the Cold War and depleted after 1991, is returning to the Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean as European and American presence in the region wanes. Will the Kremlin try to gain freer access to the Eastern Mediterranean by expanding its presence in Tartus?

Will it continue to increase its military presence in Crimea and eastern Ukraine and increase pressure on Bulgaria to reduce NATO presence while working to coordinate a reconciliation between Turkey and Russia to gain greater influence in the Turkish Straits?

For Russia, the geostrategic factors in the Black Sea region have not changed since 1853, and NATO and the United States have replaced individual European countries as Russia’s main geopolitical opponents: Crimea is a military source, Turkey is an axis, and the Turkish Straits are Russia’s main geopolitical hub.

However, the strategic axis and ultimate goal is to enter the Eastern Mediterranean and station troops there to counterbalance the eastward expansion of the United States and NATO and their presence in the Aegean and Central Mediterranean.